31

Shot of the Month – August 2021

Ok, so first of all, it isn’t that Venice.

And second, the star-crossed lovers are avian in nature, two lovely Great Blue Herons (GBHs), as shown above.

I found this pair of lovebirds at a nesting site (rookery) in the town of Venice, Florida. There is a small lake in Venice with an island of trees where the herons love to build nests and raise their families. It is a surreal to be in such a developed area and then if you turn down one particular quiet street, boom – you suddenly find nesting BGHs, snowy egrets, anhinga, and other assorted wading birds. The alligators in the lake help dissuade any predators (raccoons for example) from approaching the island so the chicks are quite safe in this urban oasis.

lake in Venice with an island of trees where the herons love to build nests and raise their families. It is a surreal to be in such a developed area and then if you turn down one particular quiet street, boom – you suddenly find nesting BGHs, snowy egrets, anhinga, and other assorted wading birds. The alligators in the lake help dissuade any predators (raccoons for example) from approaching the island so the chicks are quite safe in this urban oasis.

Standing up to four feet in height GBHs are the largest herons native to North America and they are one the most successful wading birds in the Western Hemisphere. Their highly adaptive nature allows them to thrive in a range of habitats and they can be found throughout North and Central America, northern South America, the Caribbean Islands, and even in the Galapagos Islands. Great Blue Herons rarely venture far from bodies of water but they can adapt to almost any wetland habitat and may be found in marshes (both fresh and saltwater), mangrove swamps, flooded meadows, lake edges or shorelines.

GBHs feed primarily on small fish but they can adjust their diet to capitalize on what may be found in a given habitat. They can prey on shrimp, crabs, aquatic insects, rodents and other small mammals, amphibians, reptiles, and birds. For example in Nova Scotia 98% of their diet is made up of flounder while in Idaho voles make up to 40% of the bird’s diet.

These adaptable birds can even be found in highly developed areas, like Venice, Florida as long as there are bodies of water nearby with a food source.

I visited the Venice Area Audubon Rookery during a December when the birds were just beginning their nesting season. The GBH is normally a solitary bird but they breed in colonies that can include 5 to 500 nests. Males tend to arrive at the rookery first and begin building a nest.

Nest building — It all begins with a stick:

During the mating season the Great Blue Herons perform elaborate courtship displays to attract a mate and to build bonds between partners.

Here we see two males stretching their necks to display the glorious neck plumage that develops during breeding season to demonstrate how attractive they are.

Pick Me No, Pick Me

Once the birds pair up the male flies back and forth bringing nesting materials for the female who completes the nest construction ensuring that everything is just right.

When the male returns to the nest after each sortie the couple will often perform ritualized greetings, stick transfers and a nest relief ceremony where they birds erect their plumes and clap their bill tips together.

Ceremonial Stick Handoff:

Here we have some bond-building bill clapping (say that three times fast…):

If all this fancy courtship goes well you get, ehhhh, an adorable (??!!) bundle of joy as shown below:

Ahhhh, Venice — love is definitely in the air at this birding hotspot. If you dig bird life consider a romantic get away to visit the rookery between December to May for a fascinating view of the courting ways of the Great Blue Heron and their avian brethren.

Until next month…..michael

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm, 1.4x TC (effective 850mm), f/10, 1/500 sec, -0.5 EV

Sources:

31

Shot of the Month – July 2021

Check out this month’s crazy landscape — looks like we found a dead tree on planet Mars. This other-worldly scene can actually be found just down the street (as least on a cosmic-size scale) in Wyoming on planet Earth. This dead tree is part of the ever-changing landscape at Mammoth Hot Springs (MHS) in Yellowstone National Park.

How did Mother Nature work her magic this time?

Before reaching the sprawling network of hot springs the water that feeds the site first passes through an underground formation of limestone leaving it rich in calcium carbonate. When the hot water is released into the air it cools quickly and leaves an ever growing hillside of terrestrial limestone (known as Travertine). Each day the cooling water from the springs deposits two tons of new building material creating an ever changing landscape of sculptures, terraces, and new formations. For thousands of years the hillside has grown and changed as the waterflow ebbs and shifts over time.

Ever visited a cave and seen amazing stalactites and stalagmites? Yeah, basically the same process. The process is so similar that the National Park services describes the Mammoth Hot Springs as “a cave turned inside out.”

The dramatic colors are thanks to the range of bacteria that thrive in the warm, wet ecosystems created by the springs. Each type of bacteria has its own color and is uniquely suited to a given temperature range and acidity level. Yellow bacteria indicate very hot water while greens and blues indicate cooler temperatures. Two orange colored bacteria, Phormidium and Oscillatoria can be found in MHS and may be the source of those hues in my image above.

So, if you dig the groovy formations found in caves, but are also claustrophobic, then check out Mammoth Hot Springs for wondrous geology in the comfort of the open air and blue skies.

Until next month….m

The MHS are located near the North Entrance of the park near the town of Gardiner. If you are heading to Yellowstone NP and want to learn more on how to explore the MHS check out these detailed posts from other photographers:

Mammoth Hot Springs/Guide to the Terraces of Yellowstone

Exploring Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone

Sources

Nikon D4S, Sigma 150-600mm (@ 150mm), f/6.3, 1/500 sec, ISO 1600

26

Shot of the Month – June 2021

In 2020 I spent a weekend at Mt. Rainier in search of wildflowers. Ironically, some of the most intense concentration of flowers, and color, can be found along side the roadway. Of course, this is not really the setting for a “wild” nature image that I am looking for. As I was driving from one hiking site to another I saw a Hoary Marmot along the road near a collection of wild flowers. I have seen marmots dining on wild flowers before as you can read about here.

“Oooh, a marmot in those wildflowers? That could be a great shot!”

Luckily there was a car pullout not far away so I slammed on the brakes and pulled over. I walked back along the road to the small “field” and tried to photograph the marmot. From time to time he would stand up and nibble on a flower. As the marmot scampered about I was ducking and dodging trying to

- find a clear shot;

- with lots of color;

- without showing the road nearby;

- without getting hit by a passing car.

The best way to not have the road in the image is to shoot from the road — tricky with cars zooming by. Where is the marmot? Ahh, ok. Click, Click. Take eye from camera view finder and scan the road. Any cars? Yep. Yikes, get off the road.

Ok, now where is the damn marmot? Reposition. Click, click…..Yikes, another car…

This game of hide and seek and dodge-the-car went on for a few stressful minutes. In the end the image above is the only one that kind of worked. The marmot eventually scampered off to flowers down the hillside before I could get THE shot.. The image is a bit of a mess but the photo does offer a nice impressionist sense of the glorious colors that can cover the mountainside for a few weeks each year. With a bit of software I added to the Monet-esque effect:

Mother nature does some of her finest work in the darndest places….

Until next month…..m

Nikon D4S, Sigma 150-600mm (@ 230mm), f/5.3, 1/125 sec, ISO 560

31

Shot of the Month – May 2021

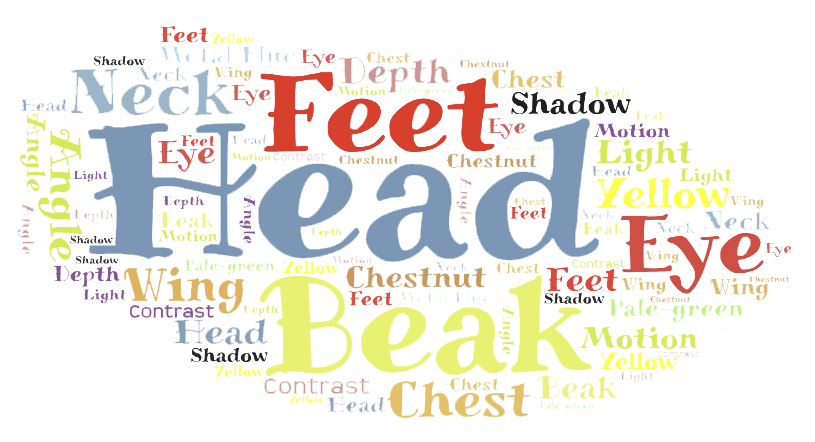

Above we have a nice image of a Grey-cowled Wood Rail (GCWR). The image is technically sound. The entire bird is in sharp focus allowing us to see the fine detail of each feather. The lighting is even making the exposure relatively easy — no areas of the image are too bright (“blown out”) and no areas that are too dark. The “flat” light ensures that the colors are accurate and pleasing allowing us to see all the beautiful colors of this South American bird.

Above we have a nice image of a Grey-cowled Wood Rail (GCWR). The image is technically sound. The entire bird is in sharp focus allowing us to see the fine detail of each feather. The lighting is even making the exposure relatively easy — no areas of the image are too bright (“blown out”) and no areas that are too dark. The “flat” light ensures that the colors are accurate and pleasing allowing us to see all the beautiful colors of this South American bird.

It’s a good photo.

No really, a really nice image.

It’s a really nice image…………………………………..that is boring.

Ok, that’s not totally fair. It would be a perfect photo to use in a Bird Identification Field Guide — in this image you can see all of the key features of the specimen and verify if it is the bird you saw. In such a book you would learn that the GCWR can be found in the forests, mangroves and swamps of Central and South America. This sounds about right since I photographed this fellow in the Pantanal of Brazil.

In such a reference guide you could learn that rails, birds that are members of the Rallidae family, are small- to medium-sized, ground-living birds. The family includes crakes, coots and gallinules and includes about 150 species of birds. This family of birds is quite diverse and can be found across much of the planet.

It is a great documentation photo and is a good image to start my GCWR portfolio. However, as this fellow sauntered about and zigged and zagged his way among the roots of the trees in the mangrove in search of a meal (most likely looking for crabs, mollusks, arthropods, frogs, seeds, berries, etc.) I managed to capture the shot below:

Wow! Although both images are of the same bird, the visual impact of the two photos could not be more different. In this shot the shallow depth of field produces a dramatic backdrop and produces a real sense of depth. That beak seems to be coming right out of the screen while little else of the bird is in focus. And the lack of definition of those red feet makes me notice them (stare really) much more than in the first image. They’re kinda creeping me out…

The portrait orientation of the image tightly stacks all of the bird’s colors on top of each other into a bewildering cacophony of hues. And the side lighting produces drama and highlights that red eye as it stares ominously at us. The angled root adds to the visual chaos. I find my eye jumping from that red foot on the root to the dramatic hues of the beak, to that red eye, and then to the chestnut body…and back to the foot, and the beak….

While I observe the first image, I feel the second. In the second image the rail becomes almost an abstract representation of a bird as the elements and colors of the bird take on a life of their own.

From the first image to the second we go from documentation to inspiration. Or perhaps from representation to interpretation? From so real to surreal? (I could do this all day, but I think you get the idea…)

Ahh, the wonders of photography — an art that can capture what we see to what we can imagine, or anything in between.

Until next month….michael

Sources:

Nikon D850, Nikon 200-400mm (@350mm), f/4, 1/1000s, ISO 6400

30

Shot of the Month – April 2021

This month we visit with the regal looking Great Egret (GE). His pose makes me laugh and I can’t help but picture a noble gentlemen of the 17th century in his long frock coat waxing lyrical about the Enlightenment and the state of the Empire.

Do you see it? Funny right?

Ok, it’s probably just me….

As I explained in an earlier post (Identity Crisis), an Egret is a Heron who happens to be all white. You can find Egrets in a range of sizes — The GE is the largest, standing almost four feet tall with a wingspan of up to five feet across.

The four sub-species of GE are distributed across the planet. One sub-species can be found in Asia, another in Africa, a different one in the Americas, and one in southern Europe. I photographed this fellow in the Ding Darling NWR in Florida so he is part of the America’s sub-species Ardea alba egretta.

Despite the 18th century similarities (at least in my head) the GE was almost wiped out in the US in the 19th century as humans hunted them mercilessly for their feathers to put in ladies’ hats.

The egret population dropped by 95%.

Because of f&@!(* hats!

Thankfully conservation efforts have allowed the population to recover in most places. Interesting fact: A GE in flight is the symbol of the National Audubon Society as the group was created during this period by outraged citizens to stop the slaughter.

I didn’t know that.

Great Egrets can usually be found in wetlands, marshes, swamps, streams, ponds, tidal flats and assorted fresh and salt waterways. These birds are super chill and are usually seen standing motionless at the water’s edge as they look for fish, their main prey; though they will also dine on amphibians, reptiles, mice and other small animals.

The GE is incredibly patient and will stand for looong periods as it waits for an opportunity to strike. I can attest to their patience as I have often lost that staring contest. For far too many times than I care to remember I have stared through a view finder with my finger poised on the shutter release button to only miss the bird’s plunge when I lifted my head for a brief second to reset my watering eyes and shift my sore neck. I am not bitter, really…

The deathblow is delivered with a quick thrust of the sharp bill and the prey is swallowed whole. Gulp.

One of the few times I captured the lightning strike. Kapow!

Curious about the dramatic lighting of these images? Learn about how it is achieved in my post Bird Art That post will also tell you more about the damn hats (with a photo!).

Despite the strong population rebound since the big, stupid hat massacre some populations of GE are struggling again. For example in the Florida Everglades the population of mating pairs of GE has dropped 90% in recent years due to urbanization, pesticide use, agricultural runoff, industrial mercury and lead poisoning. And due to illegal toxic-waste dumping, draining, dredging and road building. To name a few….

You have to admire the resilience of the Great Egret though I do hope that our continued onslaught on these birds does not force the Audubon Society to retire its hard-earned logo.

Until next month……m

P.S. Did you notice the fish in the first image?

Sources:

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm, f/11, 1/1000, ISO 6400, EV -2.5

31

Shot of the Month – March 2021

This month we visit with a small black and white bird that thrives in cold climates. From the image above you might guess that it is a type of penguin who has a flair for color and panache. Actually this lovely chap is an Atlantic Puffin (AP) and despite the similarities, he is not related to the penguin. APs are part of the Alcidae family of seabirds and they can fly (unlike penguins).

The AP is about the size of a mourning dove and weighs about a pound, which is kind of heavy for a bird of that size. The puffin is an excellent swimmer and uses that weight to help him dive up to 200 feet in search of a meal.

These birds are incredibly resilient – they spent most of their lives on the open sea in the North Atlantic Ocean which is C-O-L-D. Over half of the world’s AP population live near Iceland. Others can be found near Norway, Greenland, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Maine, western parts of Europe and northern Russia.

When out on the open ocean the birds tend to live solitary lives. Given the vast expanse of the North Atlantic Ocean, and the small size of the bird, we actually know very little about their lives as scientists can rarely find one to study!

In late spring the AP returns to coastal areas and nearby islands to breed in large colonies. During this period those striking bills and feet become super colorful to attract potential mates. Once an AP finds a partner they stay together for life, up to 25 years for some. After eight months apart the couple reunite at the same burrow site to continue their partnership. Mother Nature is such a romantic…

The mated pair work together to raise a single chick each year and the parents take turns going out to sea to look for food. In the image above you can see an adult returning back to the burrow to feed the chick.

I point to the corner of my mouth, “Excuse me Mr. Puffin you have a little something right uh, well, you have some crumbs at the edge of…….uh, never mind.”

AP dine mainly on herring, sand eels and capelin. Puffins normally swallow their catch underwater but when catching food for their chick they use their specialized bill to carry mouthfuls back to the burrow. Atlantic Puffins have backward-pointing spines on their bills, tongues, and on the roof of their mouths. They push each newly caught fish to the back of their mouth with their tongue and the fish are kept secure by the tiny spines. This allows the puffin to keep their mouth open and keep fishing for more. A puffin can usually hold about 10 fish in his mouth though in these phots I think I count 11 or 12 fish. Nice job!

when catching food for their chick they use their specialized bill to carry mouthfuls back to the burrow. Atlantic Puffins have backward-pointing spines on their bills, tongues, and on the roof of their mouths. They push each newly caught fish to the back of their mouth with their tongue and the fish are kept secure by the tiny spines. This allows the puffin to keep their mouth open and keep fishing for more. A puffin can usually hold about 10 fish in his mouth though in these phots I think I count 11 or 12 fish. Nice job!

I photographed this hard working puffin parent on Machias Seal Island, off the coast of Maine. The “full-mouth” shot is tough to capture. Once the bird lands he is running to duck into the burrow as quickly as possible as every other puffin and gull in the neighborhood is running towards him to steal his cache.

There you have it, the Atlantic Puffin – the adorable, colorful, chipmunk-esque plucky bird of the sea.

For more on the Atlantic Puffin check out my Clown of the Sea post.

Until next month…..m

Sources:

Nikon D300S, Nikon 200-400mm (@ 200mm), f/4, 1/4000 sec, ISO 200, EV -0.5

28

Shot of the Month – February 2021

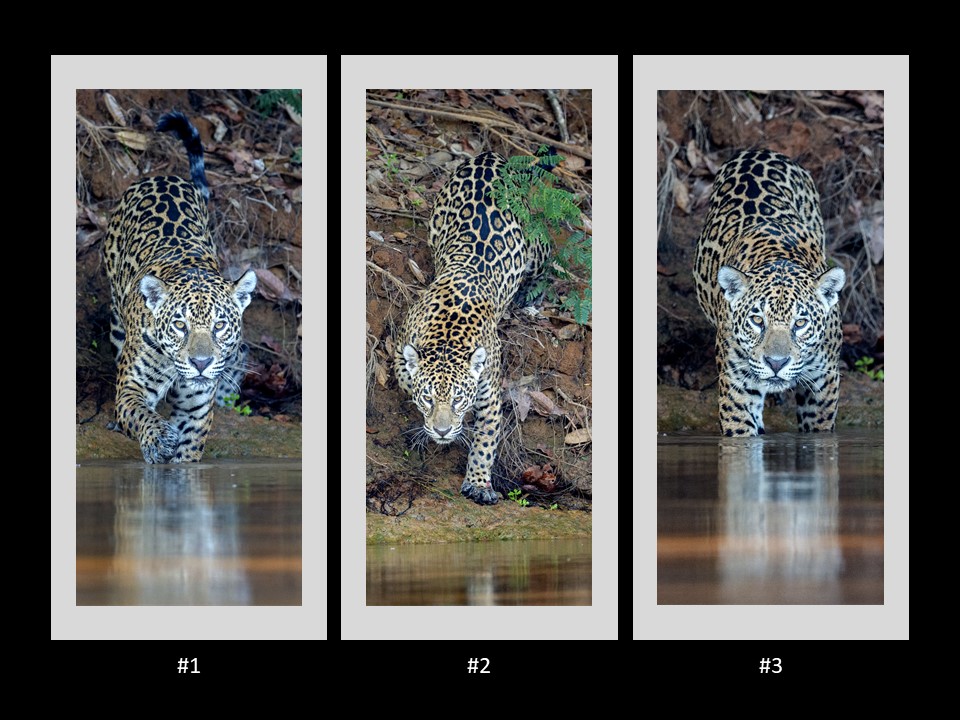

I have been wanting to post one my portrait oriented images of a jaguar for quite a while but found myself on an endless merry-go-round. I will post this image. No, this one. Hmmn, perhaps this one. Repeat ad nauseum.

I found myself faced with a “Sophie’s Choice.”

Sophie’s choice refers to an extremely difficult decision a person has to make. It describes a situation where no outcome is preferable over the other. This can be either because both outcomes are equally desirable or both are equally undesirable.

To be clear, I am not complaining — having three pretty decent images of a jaguar to choose from is a lovely conundrum to be faced with.

Our kitty carousel looks like this:

All of these images were taken in the Pantanal in Brazil. We had the good fortune of watching this female as she stalked the river’s edge in search of a meal.

Image #1:

The eye contact is pretty good but the kicker is the raised paw just about to enter the water.

Image #2:

We trade full eye contact for a menacing stare, but we do get a wonderful full-body view of those gorgeous jaguar markings. And the powerful, yet lithe, almost serpentine shape of the body – it just oozes lethal predator on the prowl.

Image #3

We find ourselves face-to-face with a jaguar. I could lose myself for days in those big ol’ eyes. And we have another good view of that stunning fur coat.

Which one would you take home?

Until next month……m

Settings for #1:

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm, f/4, 1/800 sec, ISO 2800

31

Shot of the Month – January 2021

Bighorn sheep are sheep. With big horns. And scientists refer to these creatures as, wait for it, Bighorn Sheep (BHS).

Lone, slow clap. Clap………………………………..Clap……………………………….Clap……………………….Clap.

How lazy are these scientists? Zero points for creativity.

The BHS males are called Rams. And they do, in fact, ram,

ram; verb: to strike with violence : CRASH

but we will get to that in a bit.

BHS live in the western mountainous regions of North America and can be found from the Rocky Mountains of southern Canada down to the deserts of the American Southwest. These mountain dwellers have split hooves and rough hoof bottoms giving them tremendous grip as they bound about along steep rocks and narrow ledges. Lambs are typically hunted by coyotes, bobcats, gray foxes, wolverines, jaguars, ocelots, lynxes and golden eagles. BHS of all ages are hunted by black bears, grizzly bears, wolves and especially mountain lions who are likewise quite agile even in the uneven, rocky habitat home to most BHS.

BHS live in social groups but the males live in bachelor groups while the females (Ewes) live with other females and their young. Males leave their mother’s group when they reach 2-4 years in age to join a bachelor group. Ahh, those were the days….(not really).

It is only when it is time to mate (the “rut”) when the two sexes come together. And this when the show kicks off. Just before the mating season, “pre-rut”, the males begin to battle for dominance. Only the most powerful ram will earn the right to mate with a group of ewes. And that’s where those glorious big horns come into play. Two competing males will walk away from each other and then turn to rear up on their hind legs and hurl themselves at each other ending in a mighty head bash.

In the image above you can see two rams in just this pose. Did you notice that the guy on the right actually has 3 feet off the ground to maximize his height and momentum? I photographed these two bruhs in the National Elk Refuge in Wyoming.

The resulting collision can often be heard up to a mile away. I can attest that that noise is startling and sounds like a rifle going off. Those horns can weigh up to 30 pounds and equal the entire weight of all the other bones in the male’s body. This Ram Bam session can last for hours until one male finally gives up and unceremoniously just walks away. “I’m out…”

Below, if you look closely you can see that the guy on the right is so chill that he still has a piece of grass in his mouth. Now that’s gangster. Full impact in about 0.2 seconds…

Dominance hierarchy is based on age, body size and horn size so usually the older males, typically those older than seven years old, tend to monopolize mating. Wait your turn, sonny boy…

Pre-match stare down….. “Bruh, you wanna go??!

After this glare they walked past each other and launched their attack.

There you have it, the Bighorn sheep….Bruh culture at its most sheepish. Bam!

Until next month…..m

Nikon D5, Sigma Contemporary 150-600mm (@230mm), f/8, 1/4000 sec, ISO 720, EV -0.333

Want more information (and similar bad jokes)? Check out some of my previous Posts on Bighorn Sheep:

Sources:

31

Shot of the Month – December 2020

I am on record as being a big fan of otters. When I think of “otters” I think of a collection of rambunctious weasels with an endless appetite for fun and group cuddles. Otters are C-U-T-E. Surely you recall this epic video that was all the rage a few years ago (23 million views and counting…).

There are 13 species of otters around the world and many are about two to three feet in length. And generally adorable. Mother Nature decided to supersize one of the three species found in South America and the result was the aptly named, Giant Otter. The Giant Otter (GO) can reach six feet in length and can weigh up to 70 pounds. They are also rather terrifying.

Pop culture analogy: Most otters are to Mogwai (Gizmo) as the Giant Otter is to Gremlin (Stripe). A bit rusty on your Gremlin folklore? You can find a refresher here, and also here on the breakout 1984 film.

Most Otters Giant Otters

I realize that this may seem a bit harsh, but your honor, I would like to submit People’s exhibit ‘A’ into evidence.

Wow, that is a heck of a menacing glare. The Giant Otter is thrashing an eel that he just caught.

Wow, that is a heck of a menacing glare. The Giant Otter is thrashing an eel that he just caught.

Like most otters, the Giant Otter lives and moves about the waterways in a family group as big as 20 strong though the average group size is four to eight. Below is an image I captured of a family resting on a river bank:

In the water giant otters are fearless and will attack ANY creature that poses a threat. In this video, a family attacks and kills a caiman (similar to a crocodile). I present Exhibit B for the court demonstrating the scariness of the GO.

Those shrieks, gurgles, and whines are the fodder for many a nightmare.

And for Exhibit C as to how gangster Giant Otters are, I submit my own testimony. One day while on a boat in the Pantanal, I saw a male jaguar wading through the water near the river’s bank. This is a common hunting technique as the jaguar looks for unsuspecting prey, whether it be caiman, capybara, or even fish in the river. In the other direction, we saw a lone giant otter swimming along the bank on a direct collision course with the jaguar. I got my camera ready as I imagined I was about to photograph a jaguar killing a giant otter. To my surprise, once the jaguar saw the otter he instantly jumped out of the river on the bank. He wanted NOTHING to do with that otter. I imagine if he realized that the otter was by himself he would have tried to stalk it, but he didn’t stick around long enough to find out. Even the mighty jaguar will not take on a group of giant otters in the water. Here you can see a family of giant otters scare off a young jaguar:

The jaguar holds the crown as the top apex predator in South America as a lone giant otter is no match for the 200-pound cat. However, once mobilized a family of giant otters has no rival. Locally the otter is known as “Water Wolf” or “River Wolf.” In Brazil, the giant otter is called ariranha which means “Water Jaguar” in the local Tupi language. Giant Otters primarily feed on fish, as shown in my original photo but they also dine on crabs, turtles, snakes, and small(ish) caiman.

And finally, with this image, Exhibit D. When these guys got supersized they became rather gargoyle-esque in their look. Try not to look at those googly eyes….and those webbed claws……eeek.

Despite their ferocious look and ruthless approach to outsiders, giant otters are affectionate with each other and the entire family is responsible for raising and protecting the pups. I recommend admiring the largest member of the otter family from a distance because if one happens to get too close, make no mistake, these river wolves will cut a b*&#h.

Until next month….michael

Sources:

International Otter Survival Fund

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm, f/4, 1/1000 sec, ISO 180,

30

Shot of the Month – November 2020

I initially titled this blog post “Cocoi Heron” as that is the name of the beautiful bird in the image. But even as I typed out the letters, C-o-c-o-i H-e-r-o-n I knew that that title did not capture the real essence of the shot. When I came upon this scene I gasped, not because of the bird, but because of the L-I-G-H-T. Many nature photographers talk about “chasing the light” to capture the occasional special image.

I am forever chasing light. Light turns the ordinary into the magical. (Trent Parke)

I found this bit of magic in 2019 as we visited the Pantanal in search of jaguars (video). Each morning, just before sunrise, we would load our gear into our small skiff and begin to cruise the rivers in search of wildlife. On this morning we came around a bend in the river and I gasped when I saw this scene. The light was stunning — I instantly reached for my camera as I signaled our “captain” to stop the boat immediately. The soft, delicate glow of the low-morning light perfectly lit the heron as he searched for a meal. I also loved how the heron was separated from the background giving the image a real sense of depth. These are the types of settings that nature photographers spend hundreds of hours searching for and they often only last a few moments each day.

Another axiom of nature photography is that good things often come to those who wait. A great technique to see wildlife is to simply stop in one place and let nature unfold before you. In this case, we stopped for a few minutes to allow me to shoot the scene with a variety of compositions. After shooting multiple shots in a landscape orientation I rotated my camera 90 degrees to shoot in portrait mode. At this point, I wanted to explore that wonderful reflection of the heron on the water. As I was shooting the heron suddenly plunged his head into the water and speared a fish. By pure luck, I had the entire scene already perfectly framed for this action (a very rare event indeed) and I only had to hold down the shutter button to capture the sequence. We witnessed this great behavior only because we stopped and spent some time with the bird.

On another day we found the same heron in some soft light that allowed us to really see his beautiful markings and colors and the wonderful detail of his feathers.

Those of you living in North America can be excused if you thought this was a Great Blue Heron – the two birds are almost identical and make up a superspecies. The Cocoi Heron however is only found across most of South America.

So in short, the improved title for this post pretty much sums up my lot in life — I’m just a dedicated “light chaser.” When I am not working you know where to find me — I’ll be out in some field, swamp, forest, or jungle chasing the light, looking to capture that fleeting magic that illuminates life at its most glorious. Let the chase begin!

Until next month….michael

Sources:

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm, f/4, 1/1000 sec, ISO 500