28

Shot of the Month – February 2023

If you spend much time with Bald Eagles you quickly learn that they are quite the thieving sort. In spite of their majestic, regal looks, Bald Eagles are often gangsters in fine dress.

Check out my post, Thug Life, for more info on their wicked ways.

Even when food seems plentiful Bald Eagles will attack each other relentlessly to steal food which seems counterintuitive. Why risk injury attacking another very well-armed eagle when there is so much food available?

Armed and dangerous:

Each summer Bald Eagles congregate along the Washington coast where midshipman fish are spawning. The concentration of fish can attract dozens of eagles which then can attract dozens of photographers, like me. And each summer us photographers ask the same question over and over as we watch another eagle fight or after we see one theft attempt after another.

“Why do they do this when there are soooo many fish right in front of us”?

Seems that scientists have noticed the perplexing behavior also and have been trying to solve this mystery. I found a paper, “Fighting Behavior in Bald Eagles: A Test of Game Theory,” by Andrew J Hansen that was published in 1986 where the scientists studied Bald Eagles at a site in Alaska.

Some key findings (at least from this one study):

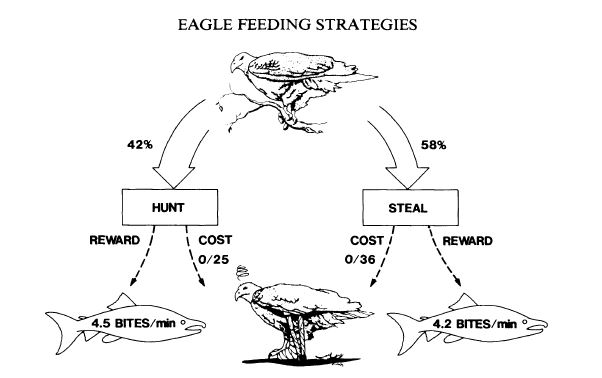

- Catching Fish = Stealing Fish

Seems that eagles that stole fish from others ate as well as eagles that caught their own fish:

Here we have an eagle catching his own fish:

2. Risk for Injury is Low

The scientists witnessed numerous attacks between bald eagles as one tried to steal from another. Surprisingly, during the study period, they witnessed zero injuries between the eagles. Despite the dramatic action the encounters rarely escalated to serious fights that can cause injury.

Eagles apparently use an array of postures, gestures and vocalizations to demonstrate both their willingness and ability to fight. Larger eagles tended to steal more often as it was clear that they were the stronger combatant. The smaller eagle would quickly acquiesce to the larger opponent and larger birds won 85% of the time.

3. Position matters:

Position was also important – a bird on the ground was always at a disadvantage to a bird coming from above in the air.

Whether a bird is positioned above or below an opponent would seem to affect it chances of winning because talons serve as the primary weapons. An aerial attacker has its feet in a position to threaten a feeder on the ground.

In the image below, the eagle on the left was sitting on the ground – at a clear disadvantage. In this encounter he leapt up to confront the attacker but as their talons interlocked the bird on the right had much more momentum and was able to flip the ground-based eagle over.

4. Communication is Important

By carefully understanding the intentions of each other, eagle interactions rarely escalate into serious battles that can lead to injury or death. Eagles will indicate their hunger level through ritualized displays. For example, in the image below we see an eagle that has thrown her head back and is vocalizing loudly — this is one of several displays that eagles can use to clearly proclaim “I am very hungry, don’t get in my way.”

The hungrier the bird, the more she will display. Other birds will see this and take this into account before deciding to attack. Or, if this bird would then go on the attack, other birds would know that she was very hungry and therefore, more motivated to fight so they might give up their meal more readily.

Fascinatingly, by throwing the head back, the eagle allows other birds to see how full his/her crop is. Another ingenious non-verbal message: “Hey, my crop is empty and I want that fish more than you do.” (A bird’s crop is an expandable “muscular pouch near the gullet or throat.” It is used to store excess food for later digestion.)

The value of a prey item to each player varies with hunger level. A bird with a crop that is nearly full can derive less benefit from a salmon than can one with an empty crop. Relative hunger level may be discernable from crop size or the length of time a bird has been eating.

Eagles apparently assessed the relative attributes of conspecifics and often chose to displace the individuals most likely to yield (small or replete birds). Pirates sometimes appeared to evaluate feeders quickly while flying overhead. Other times the birds landed and seemed to study feeders intently before attacking. The latter method may allow more accurate assessment but it is done with loss of a possible positional advantage enjoyed by aerial attackers.

At any given moment the eagles are constantly assessing size (Am I bigger?), position (birds in the air have tactical advantage over birds on the ground); and hunger level (who wants this more, me or her?) before attacking or if deciding if they should give up their fish.

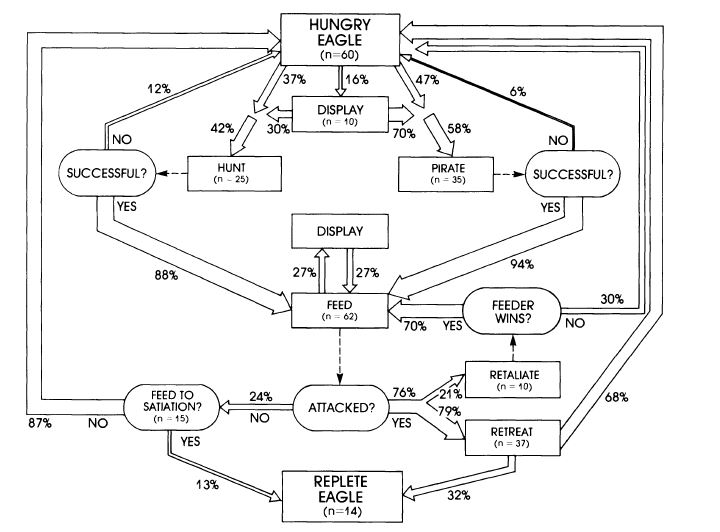

This fascinating diagram from the study attempts to map out the parameters at play:

I love the scientific insights but I love photography even more. In my first image above we see an aerial attack and some nifty flying as the eagle with the fish implements a barrel roll to confront his attacker.

Here we see the same attack, just a fraction of second sooner:

Everybody wants in on this fish:

An adult Bald Eagle harassing a juvenile Bald Eagle (The adult successfully stole the fish!!).

It seems that Bald Eagles are not the reckless pirates I thought they were. Of course, I should have known better – animals are hyperaware of their surroundings and do not take unnecessary risks. Mother Nature is far too wise for that. Each Bald Eagle is constantly evaluating its best solution for finding a meal. Each bird uses a complex array of communication and observation to switch between the tactics of hunting or pirating, in a moment’s notice, depending on which approach is most favorable for the opportunity at hand.

Game on!

Until next month……m

Nikon D5, Nikon 600mm, 1.4x TC (effective 850mm), f/5.6, 1/1500 sec, ISO 400, EV +1.0