31

Shot of the Month – March 2023

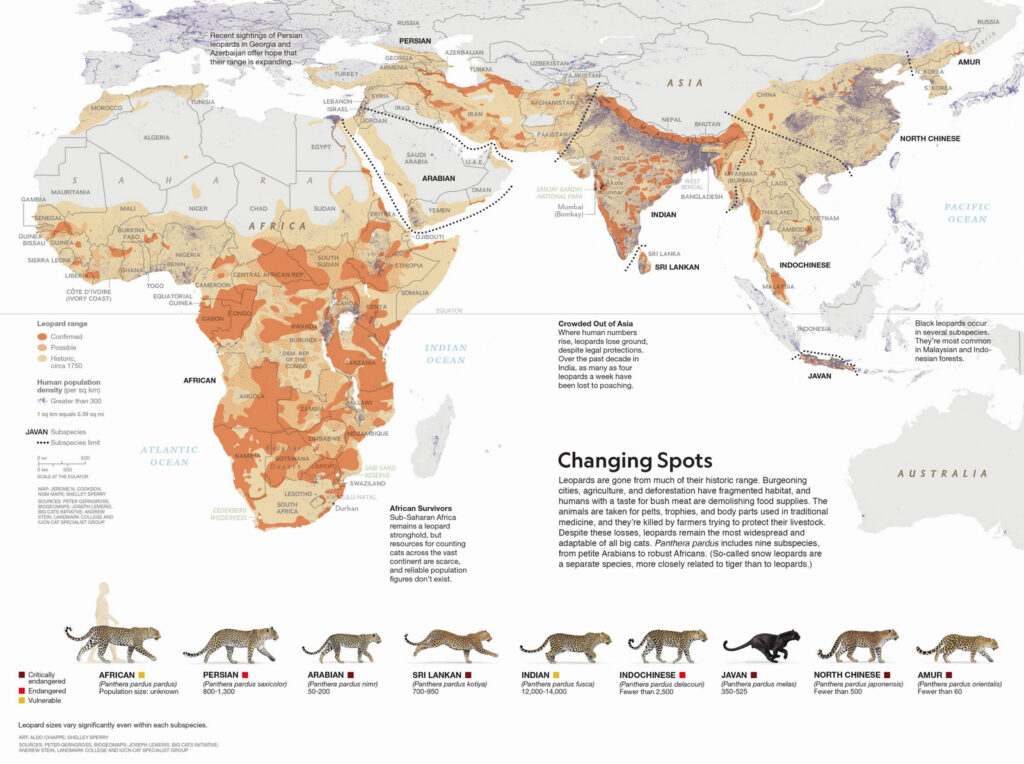

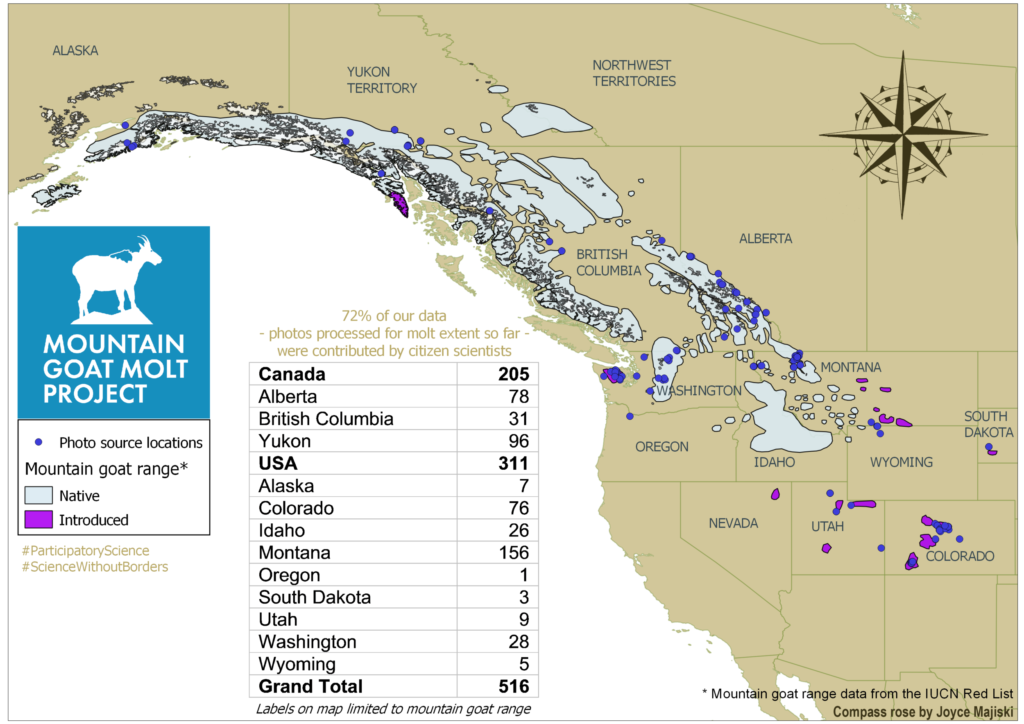

I love wild cats and I have had the good fortune of seeing lion, tiger, cheetah, serval, caracal, and the African wildcat in the wild. Of that group I am particulary partial to the leopard. Pound for pound they are perhaps the strongest of the group. Leopards are incredibly elusive and even a single sighting on a safari is a major victory. On our trip to Kenya in 2021 we had the amazing good fortune to have six leopard sightings!! I have only seen leopards in Africa but there are actualy 9 subspecies of leopard spread out across the world:

It is generally accepted that the African leopard is the most numerous species though there is no reliable estimate of their total population on the continent. India is home to roughly 12,000 leopards. Many of the other species of leopards are on the verge of extinction, however.

Individuals remaining:

Amur Leopard: 100

Javan Leopard: 250

Arabian Leopard: 200

Sri Lankan Leopard: 800

Persian Leopard: 800

Indochinese Leopard: 1000 to 2500

Leopards are stealth hunters and are renowned for their ability to carry prey up into trees to feed in peace. In the image above we found a leopard in the Masai Mara National Reserve with the remains of a Thompson’s Gazelle.

The uninitiated sometimes confuse the leopard with a cheetah. As you can see here however, the animals are quite different in size and build:

The leopard has shorter legs and a more muscular build. The cheetah (also photgraphed on the same trip) is built like a greyhound dog – long legs and a lean body. The spots on the cheetah are solid while the leopard has not spots, but rosettes. The cheetah is built to chase small prey across the open plain while the cheetah stalks in the bushes or may pounce from above while hiding in a tree.

A few more images from our trip:

A mother leopard playing with her cub just after sunrise

Another leopard with a Thomspon gazelle:

Kitty in a tree:

We found this female hunting along a riverbed just after sunrise

The color version:

The stunning leopard – its elusive magic never fails to dazzle.

Until next month….m

Nikon D5, Nikon 600mm, f/4 1/500 sec, ISO 250, EV +1.33

28

Shot of the Month – February 2023

If you spend much time with Bald Eagles you quickly learn that they are quite the thieving sort. In spite of their majestic, regal looks, Bald Eagles are often gangsters in fine dress.

Check out my post, Thug Life, for more info on their wicked ways.

Even when food seems plentiful Bald Eagles will attack each other relentlessly to steal food which seems counterintuitive. Why risk injury attacking another very well-armed eagle when there is so much food available?

Armed and dangerous:

Each summer Bald Eagles congregate along the Washington coast where midshipman fish are spawning. The concentration of fish can attract dozens of eagles which then can attract dozens of photographers, like me. And each summer us photographers ask the same question over and over as we watch another eagle fight or after we see one theft attempt after another.

“Why do they do this when there are soooo many fish right in front of us”?

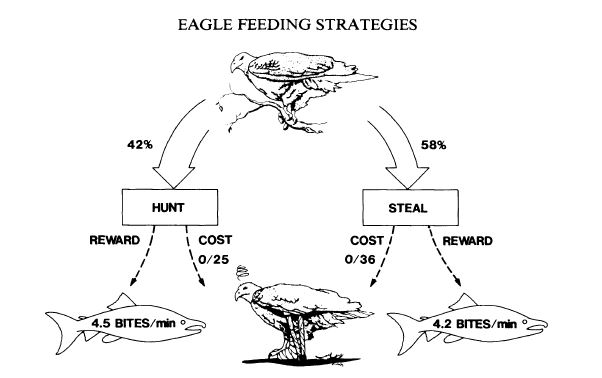

Seems that scientists have noticed the perplexing behavior also and have been trying to solve this mystery. I found a paper, “Fighting Behavior in Bald Eagles: A Test of Game Theory,” by Andrew J Hansen that was published in 1986 where the scientists studied Bald Eagles at a site in Alaska.

Some key findings (at least from this one study):

- Catching Fish = Stealing Fish

Seems that eagles that stole fish from others ate as well as eagles that caught their own fish:

Here we have an eagle catching his own fish:

2. Risk for Injury is Low

The scientists witnessed numerous attacks between bald eagles as one tried to steal from another. Surprisingly, during the study period, they witnessed zero injuries between the eagles. Despite the dramatic action the encounters rarely escalated to serious fights that can cause injury.

Eagles apparently use an array of postures, gestures and vocalizations to demonstrate both their willingness and ability to fight. Larger eagles tended to steal more often as it was clear that they were the stronger combatant. The smaller eagle would quickly acquiesce to the larger opponent and larger birds won 85% of the time.

3. Position matters:

Position was also important – a bird on the ground was always at a disadvantage to a bird coming from above in the air.

Whether a bird is positioned above or below an opponent would seem to affect it chances of winning because talons serve as the primary weapons. An aerial attacker has its feet in a position to threaten a feeder on the ground.

In the image below, the eagle on the left was sitting on the ground – at a clear disadvantage. In this encounter he leapt up to confront the attacker but as their talons interlocked the bird on the right had much more momentum and was able to flip the ground-based eagle over.

4. Communication is Important

By carefully understanding the intentions of each other, eagle interactions rarely escalate into serious battles that can lead to injury or death. Eagles will indicate their hunger level through ritualized displays. For example, in the image below we see an eagle that has thrown her head back and is vocalizing loudly — this is one of several displays that eagles can use to clearly proclaim “I am very hungry, don’t get in my way.”

The hungrier the bird, the more she will display. Other birds will see this and take this into account before deciding to attack. Or, if this bird would then go on the attack, other birds would know that she was very hungry and therefore, more motivated to fight so they might give up their meal more readily.

Fascinatingly, by throwing the head back, the eagle allows other birds to see how full his/her crop is. Another ingenious non-verbal message: “Hey, my crop is empty and I want that fish more than you do.” (A bird’s crop is an expandable “muscular pouch near the gullet or throat.” It is used to store excess food for later digestion.)

The value of a prey item to each player varies with hunger level. A bird with a crop that is nearly full can derive less benefit from a salmon than can one with an empty crop. Relative hunger level may be discernable from crop size or the length of time a bird has been eating.

Eagles apparently assessed the relative attributes of conspecifics and often chose to displace the individuals most likely to yield (small or replete birds). Pirates sometimes appeared to evaluate feeders quickly while flying overhead. Other times the birds landed and seemed to study feeders intently before attacking. The latter method may allow more accurate assessment but it is done with loss of a possible positional advantage enjoyed by aerial attackers.

At any given moment the eagles are constantly assessing size (Am I bigger?), position (birds in the air have tactical advantage over birds on the ground); and hunger level (who wants this more, me or her?) before attacking or if deciding if they should give up their fish.

This fascinating diagram from the study attempts to map out the parameters at play:

I love the scientific insights but I love photography even more. In my first image above we see an aerial attack and some nifty flying as the eagle with the fish implements a barrel roll to confront his attacker.

Here we see the same attack, just a fraction of second sooner:

Everybody wants in on this fish:

An adult Bald Eagle harassing a juvenile Bald Eagle (The adult successfully stole the fish!!).

It seems that Bald Eagles are not the reckless pirates I thought they were. Of course, I should have known better – animals are hyperaware of their surroundings and do not take unnecessary risks. Mother Nature is far too wise for that. Each Bald Eagle is constantly evaluating its best solution for finding a meal. Each bird uses a complex array of communication and observation to switch between the tactics of hunting or pirating, in a moment’s notice, depending on which approach is most favorable for the opportunity at hand.

Game on!

Until next month……m

Nikon D5, Nikon 600mm, 1.4x TC (effective 850mm), f/5.6, 1/1500 sec, ISO 400, EV +1.0

01

Shot of the Month – January 2023

Wow, check out this beast. He is an absolute UNIT.

This is one of the few images I have that starts to give a sense of how massive a Moose can be and demonstrate how majestic they can look.

The Moose is the monster of the deer family – it is the largest member of the deer family and is the tallest mammal in North America. A male moose can easily top 6 feet at the shoulders, and add in those antlers and this goliath towers more than 10 feet in height. Those antlers (males only) are often more than 6 feet wide and can weigh over 50 pounds. Moose are typically found in the northern regions of the United States (from Maine to Washington) and throughout Canada. Much of their height is due to their long legs that are essential to navigate the deep snow of winter found in their northern habitats. But these guys have length as well as height. Moose can easily be more than 7 feet in length and males can weigh from 1200 to 1600 pounds. It is difficult to appreciate how massive these creatures until you have one walk by you.

Photographically it is a real challenge to do these guys justice as they often just look like big brown blobs. In the winter they usually keep their head down as they graze – no point wasting energy raising those heavy antlers higher than necessary. In the winter it is all about conserving energy so moose will spend many hours sitting down, resting. Perhaps a nap here or there. Then, all of a sudden, they pop up and start to graze for an hour or so. During that brief period of activity a moose may only lift his head once or twice for a few, fleeting seconds. If you glance somewhere else, or turn to chat with a colleague and he looks up? Poof, you missed your shot. Come back in a few hours and try again! I have spent far more minutes than I care to add up staring through a viewfinder, with tears running down from my fatigued eye, as I waited for that “heads up” moment.

In this image it all came together. I managed to find a small ravine that put me lower than the moose. I burrowed down on my knees into the snow to get as low as I could go. This low angle allowed the male to tower over me, and seemingly, even tower over the mountains in the background. This angle also highlights those stunning antlers. Frequent visitors to Grand Teton National Park know this moose well and he is recognized as one of the biggest moose in the park in recent years.

In this shot he stopped grazing and stood fully up to take in his surroundings. Eureka, let the photo frenzy begin!

With the sun behind the clouds the lighting was soft and even. The light was strong enough to see the details of his dark brown fur while being weak enough to not overexpose those light-colored antlers. The snow on the ground acted as a reflector and bounced the light up into the moose’s face allowing us to see his eyes. Normally those big brown eyes are TOUGH to see and getting a bit of catchlight is even rarer.

The turn of the head gives a nice profile of his face and breaks up the outline of his body. The head turn allows us to see just how massive his antler are. That bit of snow on his nose also offers a nice bit of contrast and depth to the image.

Speaking of depth, the snow in the foreground leads the eye to the dark moose and overall we get a great 3D effect between the light foreground, the dark moose and then again with the light shades of the sky in the background.

I love this image so much it is currently the largest metal print we have in the house. As you head down the steps to our basement you find yourself confronted by a 30″x 40″ copy of this monster.

Even though the massive print is not “lifesize” it is big enough to give a sense of the scale of a Moose. That realization stops many a guest in their tracks as they stare in awe.

Mission accomplished….

Until next month….michael

Nikon D5, Sigma 150-600 (@150mm), 1/500 sec, f/5.6, ISO 800, EV +0.667

31

Shot of the Month – December 2022

If you want to see a Mountain Goat (MG) you are going to have to put some steps in. And I don’t mean those comfortable, flat-land steps. Oh no, that won’t get the job done. We are talking about some serious vertical steps. You gotta go up, up, and more up.

These elusive creatures thrive at elevations where few other animals roam – Mountain Goats can be found at elevations of 13,000 feet (4,000 m) or more. In the photo above, taken at Hidden Lake in Glacier National Park in Montana, I got off lucky and “only” had to climb to about 6,400 feet (2000 m) in elevation to get this scenic shot. (6400 feet is about 600 flights of stairs)

By spending much of their time above the tree line Mountain Goats can avoid most predators. When they do tread to lower altitudes they can be hunted by cougars, wolves, wolverines, lynxes, and bears. Of that list of threats, the cougar is the most worrisome as they are uniquely nimble to navigate the rocky ecosystem of the goats and are large enough to overwhelm even the largest Mountain Goat adult.

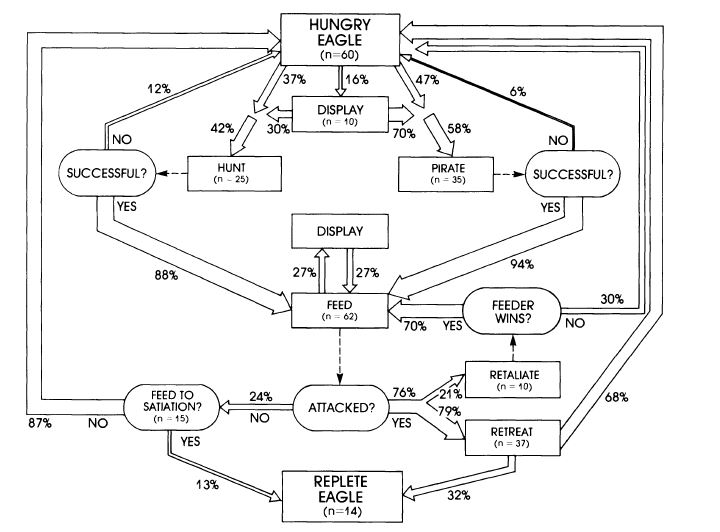

Mountain Goats are found in the alpine and subalpine environments of the Rocky Mountains, the Cascade Range, and other mountain ranges in western North America. You can find them in Washington, Idaho, Montana, and through British Columbia and Alberta, into the southern Yukon and southeastern Alaska. British Columbia is home to about half of the known population of Mountain Goats.

Mountain Goats remain one of the least-studied large mammals in North America due to the difficulty of reaching their rugged ecosystems and the creature wasn’t even mentioned in scientific literature until 1816!

Mountain Goats have been introduced, primarily for hunting purposes, into parts of Idaho, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, Oregon, Colorado, South Dakota, and the Olympic Peninsula of Washington. Several of these states are now, however, starting to remove these non-indigenous populations of goats due to the adverse impact they are having on the ecosystems and other species (read more about this here). For example, Mountain Goats can introduce bacterial disease that can wipe out the indigenous Big Horn Sheep – a species that is already struggling with various threats.

In the map below you can see the historical range of Mountain Goats and the areas where the species has been introduced by humans (shown in purple):

False Advertising:

Despite their name, Mountain Goats (Oreamnos americanus) are not goats. MGs are actually in the bovidae family so they are more closely related to antelopes, gazelles, and cattle.

Mountain Goat Nomenclature:

Male MG: billy

Female MG: nanny

Young MG: kid

A group of MGs: band

Billy/Nannie??

It can be difficult to distinguish a male from a female as both sexes sport those distinctive beards and have horns. Their luscious coats can withstand winter temperatures as low as -51F (-46 C) and winds up to 99 mph (160 km/h). Female MGs weigh about 180 pounds while the males can reach 300 lbs. The horns of the female are about the same length as the male but tend to be more slender and bend back more sharply at the tip. Mountain Goats keep their horns year-round.

Like a Tree!

You can tell the age of a MG by counting the annual growth rings on their horns which are formed each winter except for the first year. (So Age = # of rings +1)

There you have it – the fuzzy wuzzy Mountain Goat – the non-goat goat intrepid denizen of the nose-bleed section of North American mountains.

Until next month….michael

Nikon Z9, Nikon 17-35mm (@ 35mm), f/5.6, 1/1000 sec, ISO 320, EV -0.667

Sources:

Alaska Department of Fish and Game

31

Shot of the Month – November 2022

WoW! Look at that amazing animal. The power it has is mind-boggling.

Oh yeah, and that brown bear in the background is pretty impressive also.

bdbdbdbdbbdbdbd-Whaaaat?

Yep, I am actually, talking about the fish. Look, brown bears are impressive and all, but Pacific Salmon (Oncorhynchus) attain an entirely different level of amazingness.

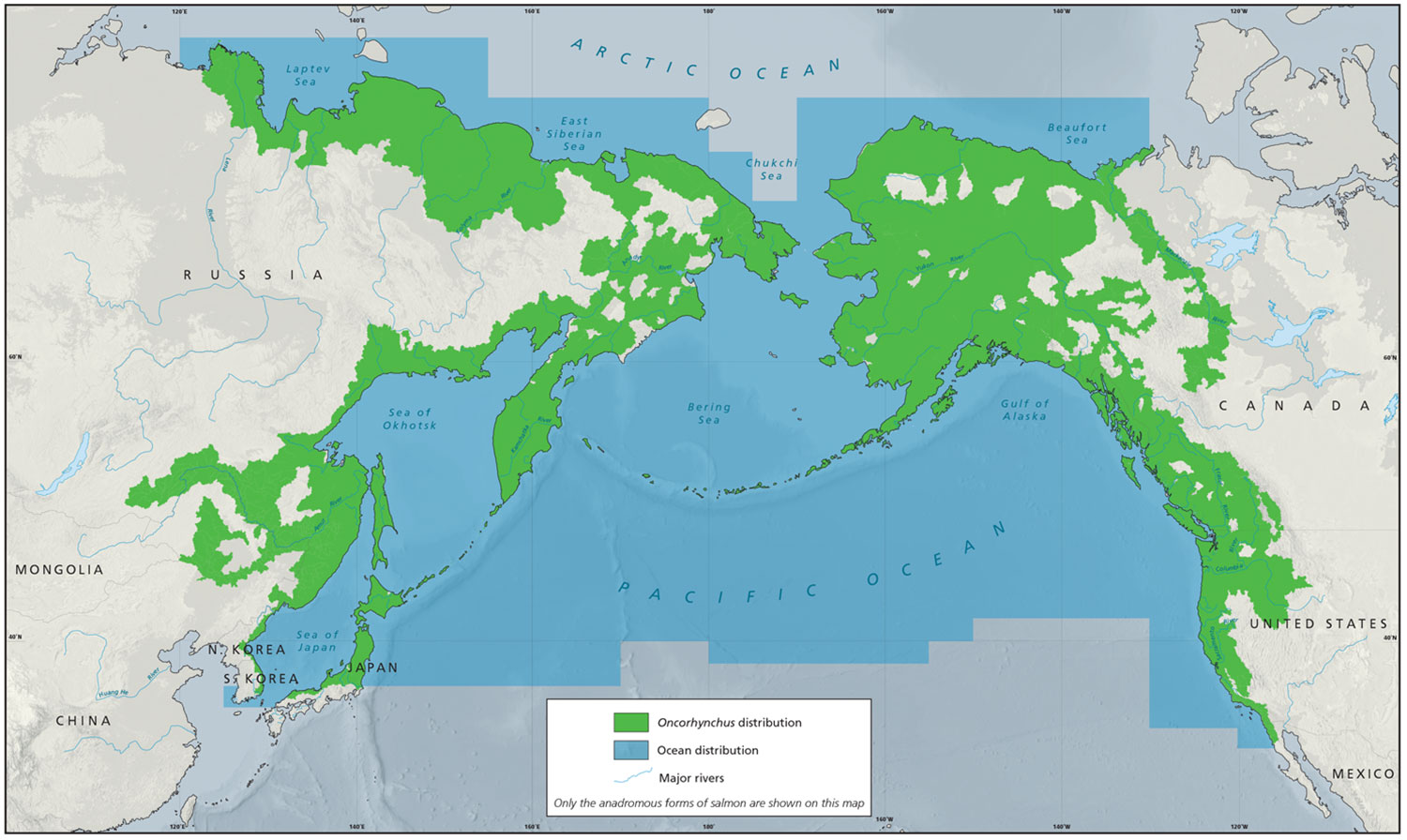

Despite their diminutive size, at least compared to a brown bear, the Pacific Salmon drives the survival of entire ecosystems across the northern Pacific Ocean as shown in this map below.

Stop for a second and let the scale of that sink in. This includes ecosystems found across thousands of miles from South Korea to Japan to Russia, across the Aleutians, and down the coastline of Alaska, Canada, Washington, and California.

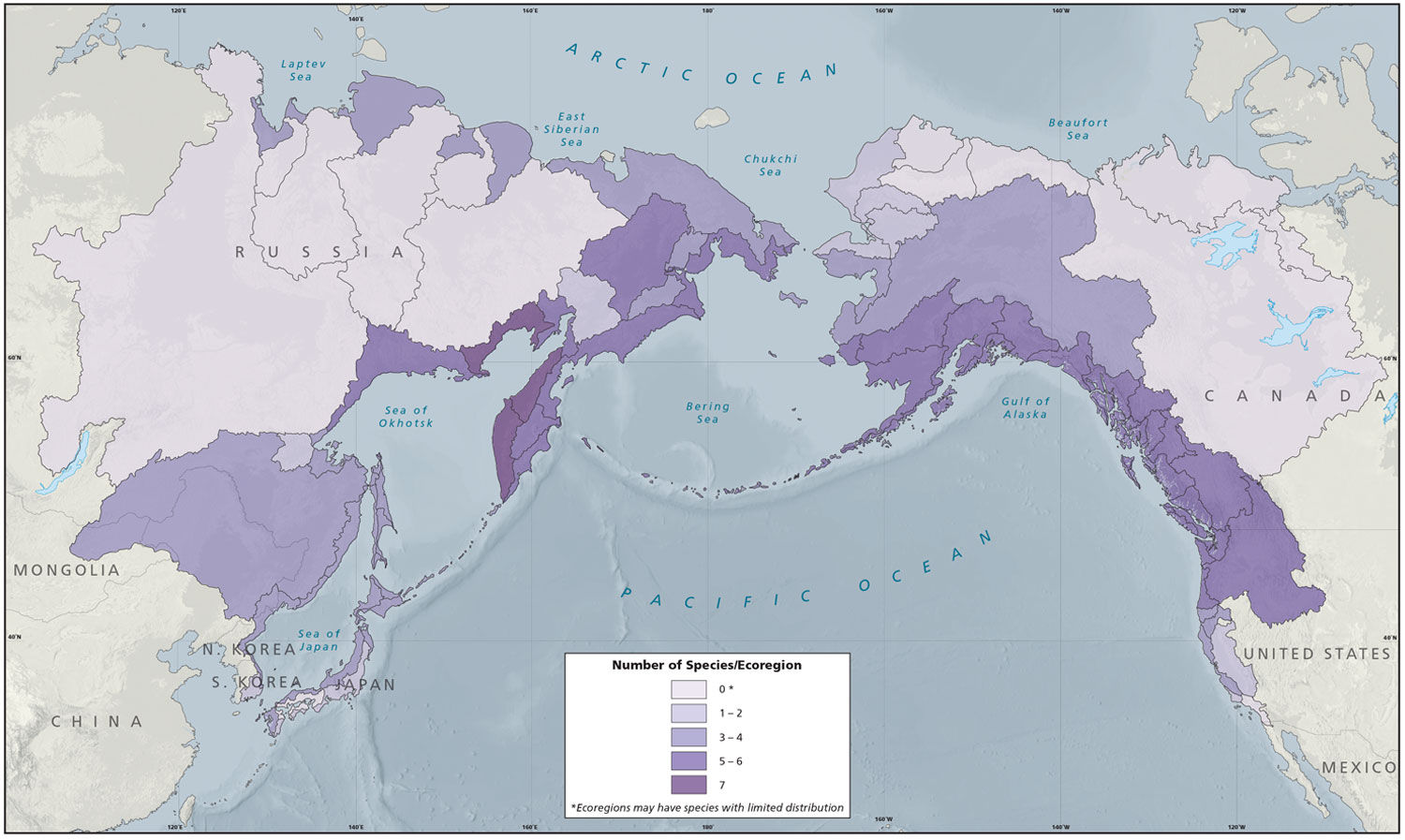

There are seven species of Pacific Salmon. Five of them are found in North American waters: chinook, coho, chum, sockeye, and pink. The other two species, masu and amago are only found in Asia. The seven species use the entire Pacific Rim coastline and can venture hundreds of miles inland in every direction from South Korea to Southern California. The coastal areas of the Sea of Okhotsk are the only regions to host all seven species as shown below.

Pacific Salmon impact so many ecosystems because of their anadromous lifestyle. Anadromous fish:

- Live the first years of their life in freshwater.

- Migrate to the ocean where food is more abundant, and then

- Return years later as adults to the same streams, where they were born, to spawn and die.

Phase 1: Freshwater to the Ocean

Pacific salmon are born in freshwater rivers and streams, and then as young fish, they begin their journey to the ocean. On this trek, more than 50% of the young salmon’s diet is insects that fall from the surrounding trees. Without the salmon there would be an explosion of insects to deal with. Salmon are the main predator of insects in aquatic environments and for this little feat alone they are Superstars. But there is more.

Phase 2: Ocean Life

Salmon gain a tremendous amount of mass while living in the rich ocean environment. As they gain mass, salmon play a vital role in the survival of key ocean species. For example, the Chinook salmon is the primary prey of the southern resident killer whale. Other ocean predators include seals, sea lions, porpoises, sharks, and lampreys to name a few. There is still more.

Phase 3: Return to Fresh Water Streams

Pacific Salmon spend 1 to 5 years in the ocean, depending on the species, before migrating back to fresh water. Each summer millions of Pacific Salmon migrate back to the streams, where they were born, to spawn and then die. The fish bring millions of pounds of nutrients from the nutrient-rich marine environment to the nutrient-poor river ecosystems. The salmon migration helps replenish the entire ecosystem, from the animals that eat the salmon, to the decomposers who break down their dead bodies, to the trees that grow from their broken-down nutrients.

For example, over 137 species of fish and wildlife depend on the Pacific salmon for survival. Of this list, 41 species of mammals rely on the salmon including orcas, brown bears, black bears, wolves, river otters and so many more. Over 89 bird species feast on salmon including bald eagles, Caspian terns, and grebes amongst others. Predators feast upon the salmon, their eggs, their carcasses, or on their young. Over millions of years, many predators have adapted their movement and behavior to take full advantage of the annual salmon migration.

In areas rich with salmon, bears will eat an average of 15 salmon/day — a significant portion of their diet. Coastal bears get 33-94% of their annual protein from the salmon. In the upper reaches of the Chilkat River in Alaska, the return of half a million chum salmon attracts thousands of bald eagles to the feast. It is one of the largest concentrations of bald eagles in the world. Wolves normally hunt for deer, but once the salmon runs start, they shift their focus to salmon. In some areas, salmon represent more than 50% of the diet of wolves.

When salmon die their carcasses provide valuable nutrients to streams and rivers.  The significant nutrients in their carcasses, rich in nitrogen, sulfur, carbon, and phosphorus, are transferred from the ocean and released to inland aquatic ecosystems. The nutrients can also be washed downstream into estuaries where they accumulate and provide significant support for invertebrates and breeding waterbirds.

The significant nutrients in their carcasses, rich in nitrogen, sulfur, carbon, and phosphorus, are transferred from the ocean and released to inland aquatic ecosystems. The nutrients can also be washed downstream into estuaries where they accumulate and provide significant support for invertebrates and breeding waterbirds.

Bears play an important role in transferring nutrients from the coast and rivers to the woodlands and forests. The bears capture salmon and feed on carcasses, and often carry them into adjacent wooded areas. There they deposit nutrient-rich urine and feces and partially eaten carcasses. Bears are estimated to leave up to half the salmon they harvest on the forest floor, in densities that can reach 4,000 kilograms per hectare, providing as much as 24% of the total nitrogen available to the woodlands. The foliage of spruce trees up to 500 m (1,600 ft) from a stream where grizzlies fish salmon have been found to contain nitrogen originating from fished salmon.

The main reason that Pacific Salmon die after spawning is to give their offspring the best chance for survival. As mentioned previously, woodland river systems along the Pacific Ocean are nutrient-poor. The rotting carcasses of the adult salmon are a major source of food for the baby fish and give them the best chance at survival. One research study showed that 40-60% of the stomach contents of young salmon could be traced to salmon carcasses. (Ewww, but, amazing)

Throughout their life cycle, salmon f-u-n-d-a-m-e-n-t-a-l-l-y transform the way ecosystems function. As predator, they keep insect populations in check. As prey, they provide essential nutrients to mammals, fish, birds, reptiles across the entire northern Pacific Rim. In death, they transfer key nutrients from the sea to inland woods needed by their offspring. But they also provide the essential chemicals that are the building blocks of entire habitats of wetlands and forests.

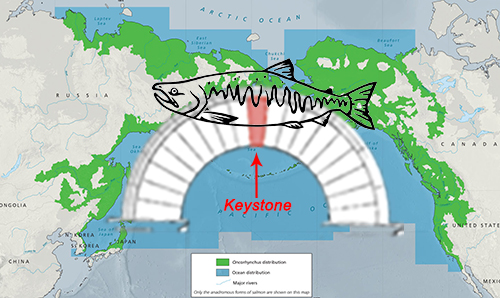

Because of all this awesomeness, Pacific Salmon are considered a KEYSTONE SPECIES.

Named for an architectural term—the keystone is the topmost stone in an arch that holds the entire structure together—keystone species are defined as species that have a disproportionately large effect on the communities in which they occur. They help maintain biodiversity and there are no other species in the ecosystem that can serve their same function. Without them, their ecosystem would change dramatically or could even cease to exist. (source)

This can’t be overstated – without Pacific salmon, many species, and entire ecosystems, are at risk for failure. We are seeing salmon populations drop in many locations, due to pollution, dams, logging, over-fishing, disease, etc. We are also seeing almost immediate ripple effects. The decline of the chinook salmon population is a major reason that the southern resident killer whale is now listed as critically endangered (only 76 individuals remain in the wild). In the US Northwest the declining salmon population is causing great stress on the populations of bald eagles, brown bears, grizzly bears, black bears, osprey, harlequin duck, Caspian tern, and river otter. To name a few. The salmon disappeared in McDonald Creek in Glacier National Park in 1981, and the bald eagle population plummeted from 600 to 25 in less than a decade. Today, salmon are extinct in almost 40 percent of the rivers where they were known to exist in California, Oregon, Washington, and Idaho. Wild Salmon have declined by 90% in Washington, Oregon, and California. Hundreds of salmon runs have collapsed across the Pacific Rim.

Normally, this is where I would end with a pithy wordplay, or a bad pun, but this situation is too serious to joke about. We need the Pacific Salmon to thrive. It is not lost on me that the coastline of the northern Pacific Rim is shaped like an arch. The keystone of that arch is crumbling. Let’s hope that humanity can act quickly to protect this Superfish.

If you want to learn more and see how you can help, check out these links:

Save Our Wild Salmon Coalition

Thanks…until next month…..michael

Nikon Z9, Nikon 80-400mm (@ 260mm), f/5.6, 1/1000, ISO 900

Sources

Ecosystem Keystone: Salmon Support 137 Other Species

Pacific Salmon (Wild Salmon Center)

Salmon: a keystone species (PacificWild)

Nature up close: Salmon, a keystone species in the Pacific Northwest (CBS News)

31

Shot of the Month – October 2022

Whoa, that is a BIG bear. Is it a Grizzly Bear? Or perhaps a Brown Bear?

Seems like a simple enough question, but as I have learned over the years, the classification or naming of critters can be a very, very messy affair.

First, let’s start with “What is a Brown Bear?”

The Brown Bear species (Ursus arctos) is the most widely distributed bear across the globe. They can be found in many countries throughout Europe and Central Asia, China, Canada, and the United States. There are approximately 200,000 brown bears in the world; with Russia having the largest population at 120,000 bears. North America is home to about 55,000 brown bears; wherein Western Canada has roughly 25,000 bears, while the United States has about 30,000. Most of the U.S. brown bears live in Alaska (about 98%) with a small population found in Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, and Washington. (source)

Next, “What is a Grizzly Bear?”

Grizzly bears are only found in North America and many feel that they are simply brown bears. Some say that they are a sub-species of Brown Bear. Others say they are a separate clade. Yeah, let’s not go down this rabbit hole or we may lose our minds…

In common usage, meaning not using any fancy Latin words, most folks go with this explanation:

The grizzly bear is a kind of brown bear. Many people in North America use the common name “grizzly bear” to refer to the smaller and lighter-colored bear that occurs in interior areas and the term “brown bear” to refer to the larger and typically darker-colored bear in coastal areas.

Did you catch that terrifying nuance? Grizzly bears, as huge as they are, tend to be the SMALLER version of brown bears. Why is that you may wonder? Brown bears, given the “definition” above, tend to live along the coast and therefore have access to salmon which provide a tremendous calorie boost to their diet, allowing them to grow to massive proportions. Have you heard of the Fat Bear Contest (check out this video)? Yeah, those are Brown Bears, who are all getting fat on salmon. Alaskan Brown Bears, like the female I photographed in Katmai NP above, can eat 80-90 pounds of food/day gaining 3-6 pounds of fat each day in preparation for hibernation.

So grizzly bears are just North American brown bears that are found in forests, interior landscapes, and other places where one cannot dine on salmon. Below is one of those “small” grizzlies that I photographed (read more about that here) in Yellowstone NP a few years ago:

Male grizzlies tend to max out around 400 pounds (females at around 250 pounds) while brown bears can reach double that size. Take all this weight talk with a grain of salt as brown bear/grizzly bear size and weight can vary dramatically depending on location/climate/diet/genetics. The Yellowstone grizzly that killed the elk in the image above, Grizzly 791, is one of the biggest seen in the park and weighs about 600 pounds so he obviously did not get the memo about being smaller.

And where does one find the biggest brown bears? That would be on Kodiak Island in Alaska. The Kodiak bear is a recognized sub-species of brown as they have been isolated from other bears for about 12,000 years – since the last ice age. Those bruisers can reach 1,700 pounds. Yelp.

So if you managed to follow all that, we can say, for the most part, that all grizzly bears are brown bears, but not all brown bears are grizzly bears. And for their size, all we can say is that brown bears and grizzlies are always big. And sometimes really big. And other times, terrifyingly big.

And I didn’t even get into the fact that “Brown” bears are only sometimes brown in color (can vary from almost white to dark tan and everything in between)…..but, my head hurts, so let’s save that for another day.

Until next month….m

Sources

Brown Bear (National Geographic)

Brown Bear (Alaska Fish and Game)

Nikon D5, Nikon 24-120mm (@ 32mm), f/11, 1/350 sec, ISO 360, +0.333 EV

30

Shot of the Month – September 2022

I sat in front of my computer scrolling through thousands of images. Scroll. Scroll…….Which image should I write about this month? Scrolling…..scrolling. The photo above crossed my screen and something about the image caught my eye and I stopped.

This image, taken in Yellowstone in 2014, had been on my computer for 8 years and I had done nothing with it. But I hadn’t deleted it yet so I must have seen something of interest way back then. I enlarged the image to fill my screen.

I stared at the photo pondering, “I like this image, but why?” “What does my subconscious see that I can’t put words to?”

I interrogated myself.

Brain: “What is the subject of this photo?”

Me: “It is a picture of bison.”

Brain: “OK, sure, there are bison in the photo. But, it is not a very good image of bison. The bison in the back is completely out of focus. The bison in the front is in sharp focus but we can’t really see his eye so we can’t make much of a connection which is usually essential for a compelling image.”

Me: Sigh, “True”

Brain: “What else??”

Me: “Well, I see a lot of snow. The bison are framed by snow on the ground. The air is full of heavy snowflakes. In fact, one could argue that the snowflakes are the dominant element in this image.”

And then it hit me. (One could say that the answer came into focus, but that would be a terrible photography pun, and I wouldn’t do such a thing…. 🙂 )

This photo captures not a thing, but reveals a relationship. It tells a story about a struggle. About a fight. Bison face many threats to survival – we mostly hear about the challenges they face from predators like wolves and bears. This image however highlights yet another threat they face, this time, from the very environment they live in. Winters in Yellowstone are long and taxing and many animals do not survive them. In fact. wolves tend to thrive in late winter because prey animals like elk and bison are easier to catch due to their weakened condition.

The elements of this image capture that struggle well. Winter is on the attack – the bison in front had its head lowered as it trods forward, enduring the onslaught. Its body is covered in snow, and the heavy snowflakes obscure much of its being. And the bison in the back is completely blurred while the snowflakes falling around him are in sharp focus. The shift in focus drives home the attack on the lumbering beast. Is he losing the battle and simply fading into oblivion?

The bison counter the offensive by taking refuge in and near the river. Why? The grass they need to eat to survive is buried under deep, heavy snow during much of the winter. However, the snow is less deep right along the banks of the river so the bison forage there, as shown below, as they have to expend less energy to reach the grass. Smart.

While not as dramatic as a cheetah chasing a gazelle, the first image nonetheless captures an epic life-and-death struggle that has played out for millennia. The heart-pounding race between gazelle and cat can be over in seconds. Winter’s attack drags on for days. Weeks. Months. Winter’s pursuit is tireless and unyielding. Freezing temperatures. Howling winds. Whiteout snow storms. Treacherous ice. Tons of snow blocking every move. Day after day after day after day…

For their part, the bison have adapted both their bodies and their behavior to give them the best chance for survival. (Sidenote: Alas, the photographer was not well adapted to these conditions. Nearly a decade later I vividly remember how my frozen hands felt like they were on FIRE after shooting this sequence).

Here is the battle in black and white:

Another view of the combatants, first in color:

And in black and white:

Bison in winter, an Elemental Struggle of the ages.

Until next month……m

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600mm, f/5.6, 1/1000 sec, ISO 1000, EV +1.33

31

Shot of the Month – August 2022

Shhhhhhhhhhhhh……ooh, how delicious. I feel like one of those paparazzi photographers spying on the rich and famous. Peering through the bushes with my high-powered lens to capture an illicit embrace. To get this shot I did lie on my back with my lens resting on my knees – it was the only way to shoot through that small opening in the branches and leaves.

What we actually have here is two lovely Cedar Waxwings performing a courtship ritual known as “courtship feeding.” Usually, it goes down like this:

The male goes off and finds a suitable gift – this could be a piece of fruit, an insect, or even just a flower petal.

He flies over to the female and lands on the same branch. He hops, hops, hops his way over next to her.

He offers the gift. If she digs the guy she will accept it. Now she hops, hops, hops down the branch away from the male.

She then hops, hops, hops back over to him. She offers the gift back to the male. He takes it.

And now repeat, many times. Eventually, the female eats the gift.

The male will go off and find another worthwhile gift and the courtship continues. And if all goes well…..well, you know. Baby waxwings…

Below, this time in black and white, we have the same pair handing off another gift:

On a different occasion, I found two waxwings in a similar pose. The birds were highly backlit so it became this silhouette:

Remember this childhood taunt?

Jack and Jill

Sitting in a tree

K-I-S-S-I-N-G!

First comes love

Then comes marriage

Then comes baby

In a baby carriage!

I am starting to get an idea of where that came from…

Ahhh, courtship feeding – a time-tested strategy shared by bros and birds alike.

Until next month…..m

Check out these videos if you want to see some courtship feeding in action:

And here is a previous post I did on Cedar Waxwings.

Nikon D4S, Nikon 600 mm, f/4, 1/1000 sec, ISO 3200, +0.333 EV

31

Shot of the Month – July 2022

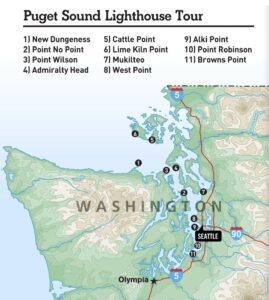

The Lime Kiln Lighthouse, shown above, is located on the western side of San Juan Island and is in just the right spot to accentuate a sunset image (#6 on the map below). The lighthouse was built in 1919 and still serves as a navigational beacon to those sailing in the Haro Strait. This location is also known as one of the best places in the world to view whales from land. Orca whales can often be seen swimming by from May to September each year. From this lovely spot, one can also see Minke whales, porpoises, seals, sea lions, otters, and bald eagles.

I arrived at the lighthouse a good hour before sunset to get the lay of the land and try and explore potential compositions. The water was unusually calm and as the sun slowly set I had an amazingly peaceful hour sitting on the rocks listening to the gentle sound of the water caressing the shoreline. Ahhhh….seaside serenity at its best.

As the sun slipped below the horizon the scattered clouds began to explode with color.

The clock had started — Time to MOVE!

Non-photographers may not realize that one does not simply walk up to such a scene, raise the camera, snap a few shots, and go home. No, usually there is an absolute frenzy of activity behind the camera that beguiles the serenity before the lens.

In my case, I was running from one outcropping of rocks to another and frantically adjusting my tripod to find JUST the right position and composition. This tripod leg up a bit. This leg, down a bit. That leg has to go over there. Nope, this leg is now too low. Raise again. Now the horizon is crooked. Adjust the camera. And all that is even before figuring out the proper exposure settings. Once the camera is in the right position I then run through a range of different shutter speeds and apertures to find the best combination that can expose the bright sky while trying to keep the exposure on the building from going too dark. For this image, I also took a series of shots at different exposure levels that I merged later with software to capture the full range of brightness in the scene. For more on how that is done, check out this post I did on photographing a lighthouse in Maine.

Ok, got that particular shot? Now rush over to a different outcropping and do it all again.

With each moment the light is changing and the colors may be getting better, or worse. With each second that is passing, I am scrambling to maximize what the scene is offering in THAT moment.

This race with the light may last mere seconds, or can go on for 45 minutes. The pressure/stress can be intense to seize the fleeting moment before it is gone.

Either way, by the end, I am usually exhausted.

But so much fun!!

Is the running around worth it? Sometimes yes, (usually yes), sometimes not.

On this outing, I captured several scenes that I really liked. In the above image, we have a classic seascape that oozes serenity and calmness. It is like a visual sigh for the soul.

But in the image below, I found a completely different story and feeling:

By moving closer, I still captured a seascape with a dramatic sky, but now I found a more intimate scene as the couple on the right becomes more prominent in the scene and turns this into a love story. The upper image will most likely have the viewer looking outward to the world while the second image will nudge the viewer’s mind inward as s/he remembers a similar sunset embrace.

Photography is about storytelling and by continuing to move around the scene I was able to find two lovely, but very different, stories. On this night, I was able to go from Landscape to Lovers in just a few feet.

Until next month…….

Nikon D850, Nikon 24-120mm (@24 mm), f/10, 1.0 sec, 7 shot Bracket (HDR merge)

30

Shot of the Month – June 2022

The natural world is filled with stunning beauty. I am certainly drawn to it and spend much of my free time trying to capture it with my camera. However, surviving in the wild is not for the faint of heart as life in the food chain is an endless battle between predator and prey. Many of us are attracted to the predator as we admire their cunning and specialized skills. Others root for the prey, especially if said prey is cute and cuddly.

In this post, I will share images where the predator was successful. This post will not be for everyone – if you are squeamish and don’t like to witness this harsh reality, I suggest you skip this month’s images.

In 2021 I went on a safari to Kenya that was focused specifically on the big cats. We would spend hours searching for lions, leopards, or cheetahs with hopes of witnessing those epic life-and-death struggles. The trip was so “successful” on that front that by the end we were quite traumatized by the amount of death we witnessed. We definitely experienced PTSD – Post Traumatic Safari Disorder. During a 10-day period, we saw a life-and-death struggle almost every day and sometimes several times a day.

Cheetah Mother and Cubs

We spent many hours over several days with this cheetah mother and her three cubs. The female was absolutely stunning looking and was by far the most impressive cheetah I have ever seen. Cheetahs are often timid and skittish. Not this female. She was powerfully built and walked with a confidence and swagger, unlike anything I have ever seen with a cheetah. Every day she had to find a meal for her growing cubs and we saw her hunt several times. In the image above mom caught a young impala but she did not kill it. Rather, she called her cubs over to have them learn/practice how to suffocate their prey. It was a tough scene to watch as the cubs didn’t know how to effectively apply the neck bite and the death was slow and drawn out. While it was a sad end for the impala, the cheetah mom had again provided essential food for her family and taught her cubs important life skills that they will need if they are going to survive on their own.

Piglets

One morning we drove to a location where we heard that two cheetahs had been spotted. As we approached we saw a couple of other vehicles sitting nearby. We had no idea where the cats were but we surmised that the cats must be sitting or lying in the tall grass in front of us. We stopped the vehicle and prepared ourselves for a long wait. But only five minutes later…

“Holy Crap!!” A warthog mom and her two piglets appeared out of nowhere and trotted down the path towards us not realizing the danger that lurked nearby.

After a brief stop, the warthog family continued down the road. The two cheetahs exploded from the grass. Mom warthog bolted straight ahead while the piglets ran in the opposite direction. The two cheetahs began chasing Mom but after a few yards, they stopped. The cats realized that the easier meal was behind them. The cheetahs changed direction and moments later each had caught a piglet.

In the blink of an eye, the mother warthog lost her entire family. In this image, we see the two cheetahs fighting over one of the piglets:

Young Topi and Young Lion

Near the end of a long day, we found a pride of lions stalking a herd of Topi that was about 100 yards in front of our vehicle, a bit off to the right.

While waiting I looked behind our vehicle and saw an adult Topi that seemed to be bleeding. I looked through the binoculars and saw blood on her rump. I said, “Hey look, that adult must have been attacked by a lion but managed to escape with those fresh wounds.” My partner took the binoculars and said, “No, she just gave birth, the newborn is lying just nearby. That blood is the afterbirth.” What a wonderful surprise.

Our joy was short-lived.

In the next moment, a young lion cub appeared and ran over and grabbed the newborn calf – most likely his first kill as a very young lion. The young calf’s “circle of life” was complete in just a few minutes and this emotional roller coaster left us reeling as we careened from joy to horror in seconds.

It was quite dark when I shot this image so the shutter speed was quite slow – the motion blur helps soften this Shakespearean tragedy – a bit. This was a particularly traumatic day – our day started with the warthog piglets and ended with the topi calf.

But the day had one last surprise. While watching the young lion run off with the topi calf we heard a commotion back out in front of our vehicle. We drove over and found that the stalking lion had just captured an adult topi.

A very tough day for the topi herd.

But don’t let these selected stories mislead you – we saw multiple other encounters where the prey won the day. Life is a struggle for all wildlife, predator and prey alike. In reality, the vast majority of predator hunts end in failure. Likewise, most young lions, leopards, and cheetah cubs never make it to adulthood.

I admire the beauty in both sides of the struggle. And I take solace that with each life lost, the “sacrifice” allows others to survive and keep the ecosystem in balance.

Ok, I promise, next month, definitely something cute and cuddly…

Cheetah Mom with Cubs (Nikon D4S, Nikon 200-400mm, f/5, 1/4000s, ISO 720